Yellow Leaves Do Hang - Esther

On Monday, I heard myself say the words we all dread in Scotland.

“It feels AUTUMNAL.”

My partner replied, “It begins.”

Because although there may be some more lucky days of sun, perhaps even a

miniature heatwave in September, we understand that once “it feels autumnal” we’re

on a one-way track to the apparently endless season of perpetual night. Autumn

is my favourite season however, not least for its choice of colours & if

one colour bridges the gap between summer & autumn, it’s yellow.

In different cultures, yellow is a symbol of wisdom & intelligence, is often used in religious art & is emblematic of gold, divinity or light. It is used in the wider world to represent freedom & for high visibility in health & safety equipment & clothing. We use it in idiom to denote cowardice & to advise slowing down. Think of the use of yellow in art & we might picture Vincent van Gogh’s various sunflower paintings or Andy Warhol’s Velvet Underground banana. We might consider Gustav Klimt’s gilded works, but gold is for another time. There is plenty of yellow art to choose from.

Less prolific with the gold, Klimt’s fellow Austrian & sometime

protégé, Egon Schiele (1890-1919) is known for his use of earthy, natural

colours, including yellow. Here in these Portraits

of Max Oppenheimer, he has painted the skin of his associate & artist

studio-mate in a yellow hue, lending the sitter a decidedly unnatural appearance.

His Yellow City however describes

a warm but cluttered urban scene. Whilst on the surface it might appear straightforwardly

cosy, with Egon there is always the danger of darkness & disturbance &

one wonders what happens behind those windows in those claustrophobic streets…

I’m sort of reminded of a book from my childhood that is now sadly lost

& which I can’t remember the details of. I can remember one page though. The

book told the story of removing all colours but one at a time with the result

that everyone suffered different ill effects depending on the single colour

inflicted on them. Each time the world changed a colour, the illustrations

showed everything coloured the same. The only page I remember was when the

world was turned entirely yellow when everyone became sick & felt queasy.

One of Scotland’s best-known modern painters was John Bellany (1942-2013)

who painted his own sickness & queasiness to perfect effect. 1969’2 Gates of Death depicts his life in

illness. Diagnosed with liver disease some years later, Gates of Death predicts the physical jaundice associated with the

condition & a figurative jaundice accompanying the indignities of any serious

illness, where we may feel isolated & robbed of our humanity &

independence.

The joyful & exuberant aspect of yellow is perhaps best expressed in

public installations such as Florentijn Hofman’s (1977-) Stor Gul Kanin (Big Yellow Rabbit) or Urs Fischer’s (1973-) Giant Yellow Teddy Bear. The element of

surprise, the enormity of the pieces, the juxtaposition of the sculptures in a

busy urban setting all contribute to these being humorous absurdist works. In

response to the assumed question “why?” the artists ask “why not?”

James McBey (1883-1959) was a Scottish master of depicting yellow heat –

abroad of course. Here his glamorous wife Marguerite

McBey, herself an artist basks in the bright sun. Aberdeen was gifted many

of McBey’s works by Marguerite, many of which portray the life & people of

Morocco. She herself referred to the location as having a “leisurely tempo”

& “dramatic ambience.” The yellow here may denote intense heat but it also

describes an atmosphere of languid, moneyed inertia. It reflects too Marguerite’s

inner warmth, corroborated by her close friendships & benevolence to a

range of institutions in Tangier, Aberdeen & the US.

Rather than his sunflowers, here is Vincent’s (1853-1890) Wheat Field Behind St Paul Hospital With a

Reaper. In recent years, the reason for his colour choices have been

pondered, researched & studied. From drug-taking to pigment availability,

there have been several theories, xanthopsia being one. This condition causes a

yellowing of part the eye itself resulting in seeing things in yellow.

Historically however there is evidence in his letters of conducting experiments

in colour to create different effects in paint. One of the more peculiar hypotheses

is that he may have eaten yellow paint. Although he admitted to eating paint

when in altered mental states, it seems the colour wasn’t important…

It would be remiss to discuss yellow in the art world without mentioning The Yellow Book, a quarterly publication

covering literature, illustration & visual art duplicates. In Victorian

Britain, yellow came to represent excess & pretention partly due to the

Decadent movement & this notorious magazine. Fundamental to The Yellow Book’s success &

notoriety was the art & person of Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898), its art

editor & contributor as well as erstwhile illustrator of Oscar Wilde’s

writing. It was purportedly Beardsley’s idea to produce the book covers in

yellow in line with the French aesthetic associating the colour with debauched

fiction. As Wilde became the epitome of depravity in England, so Beardsley fell

out of favour at The Yellow Book. His

influence is indisputable thanks to his exquisite images & The Yellow Book cemented his reputation

as a fabulous peddler of filth.

Sofia Minson’s (1984-) Rose of the

Cross is a beautiful modern-day icon. A monochromatic head highlighted with

yellow/gold patterning & glowing halo, it recalls traditional religious

iconography & European painting & combines these with Māori

portraiture. The subject’s moko on

her chin & forehead identify her as Māori & are a sacred assertion of

her integrity & history. Minson’s work celebrates her mixed heritage &

integrated cultures & honours different aspects of diversity in her portraits.

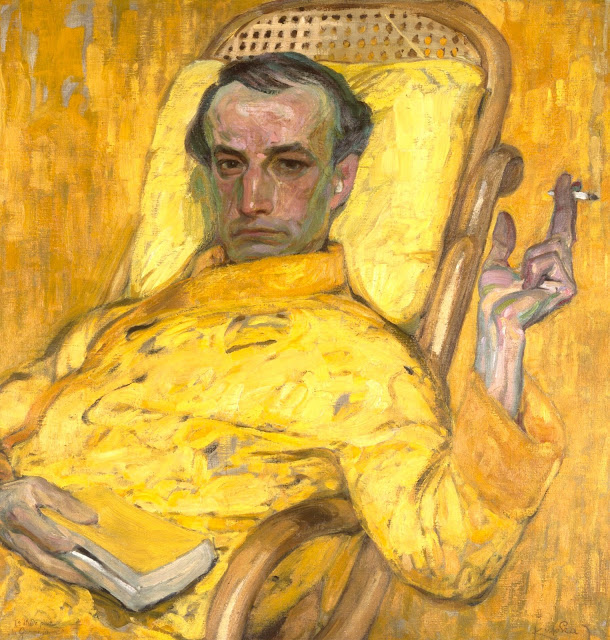

My personal favourite yellow artwork however is the visually imposing, technically brilliant & highly expressive The Yellow Scale by František Kupka (1871-1957). In fact containing several (well-mixed) colours, this masterpiece depicts the artist lounging in all his indolent glory. A self-portrait perhaps, but the true star is the colour yellow. Another experimenter in colour theory, Kupka’s interests verged on the esoteric & despite remaining committed to representational works, he nevertheless investigated the poetic & scientific properties of colour.

Here he has mastered the art of blending the realistic with the expressive. The sensual – or is it aloof? - gaze, as if he’s about to speak. To sniffily berate us for interrupting his smoking/reading peace or to invite us out for a night of heavy drinking? Whatever the intention, there’s an undeniable element of “look at all I can do with one colour…” We’re impressed, as is surely Kupka’s intention. The unity of composition through colour is rarely rendered so expertly & in my opinion never bettered. In yellow or anything else.

Once again, a welcome art lesson. A vast field of knowledge where each excursion mostly reinforces how few landmarks I know. Much appreciated.

ReplyDeleteYellow, in people and plants, most immediately conveys illness to me. Jaundice (even though life experience has shown me that someone with liver failure can become pumpkin orange, as I saw with one, comatose sister-in-law) in humans and both in fall transition and over-watered plants – the latter of particular attention to me in this year of pandemic-driven container gardening missteps.

The browned yellows of Yellow City have a borderline unpleasant aspect for me (probably more revealing of myself than anything else), as it triggered a biting sense memory (smell) of fabric drenched in urine and allowed to dry.

How constant are the colors of many of these works? How chemically stable the media they’re rendered in? Is there a consensus on any changes wrought by oxidation of the medium and turns of pH in the canvas? I imagine it’s a concern as people a century and more later stop to wonder if they’re seeing what the artists and their contemporaries saw when these works were new. Even many photographic processes proved to be less color-fast than originally hoped, so we can’t even necessarily rely on photographs of these works when it comes to hues. I imagine art scholars revisit the notes of reviewers from the period to try to get a better sense of this -- of what they were seeing.

One of the biggest problems I have with the pictures I post are that there are a lot of bad colour reproductions, but it helps if I have seen them in "person" to be able to match them up, e.g. the Kupka, the McBey & the Schieles.

ReplyDeleteWhen I was researching aspects of this post, it was noted that yellow is rarely a favourite colour "in the West." It has different connotations in different places.

I'm not sure of the colour stability & I'm always learning about the science, but of course a lot of old paintings have had varnish layer after varnish layer piled onto them which yellows them really badly, to the point of brownness at times. Some are completely changed compositions as a result. When you consider that varnishes were often only meant to last 20 years or so, it's no wonder restoration is such a skill & can take so long!